Special Guest Post by Michelle Marie Robles Wallace.

Ingrid Hernández is a visual artist and sociologist based in Tijuana, a city bordering the U.S. that is one of Mexico’s fastest growing metropolitan areas. Hernández has been using her camera to document the raw edges of that growth – the areas outside the city limits where people build their houses on small plots of land with whatever materials they can find.

A home with cardboard walls from the “Tijuana Comprimida” series – Photo: Ingrid Hernández

(See more images on her website.)

Hernández did not plan to become an artist, but after she obtained her masters degree in social science, she started taking long walks every day through the north-eastern part of Tijuana, where the city sprawls out in new, unincorporated and self-governed communities. In the Nueva Esperanza (New Hope) neighborhood, she saw homes with walls made of recycled garage doors, sheets, and the pressed cardboard from the backs of old TV sets.

She started taking photographs without intending to make anything in particular, but after several months, she noticed that she had not taken a single photo of people. She had taken pictures of the buildings, focusing on the materials people had used to construct them.

Hernández realized that she was interested in the houses because they revealed so much about the people who built them. She noticed that they built their homes in the style of their homeland; that “the people of Veracruz constructed in a manner distinct from those of Chiapas.”

Once Hernández saw this, she had the “clarity to begin a project…that spoke a lot about the places people came from.” Over the next three years, she built relationships within the community at Nueva Esperanza, conducted interviews, documented their buildings and finally, combined her photographs with the interviews in a book, Tijuana Comprimida, which was put on display at el Museo de Arte Moderno (Museum of Modern Art) in Mexico City. Images from the Tijuana Comprimida series can be viewed on Hernández’ website.

Hernández’ strength as an artist comes from her training in the social sciences—her work focuses on how people live, who they are, and how they form community. Her images and texts explore the lives of people who do not have access to municipal sources of water or electricity, and show their artfulness in working with what is available. The lime green paint that highlights the raised design of cartons-turned-walls, the thoughtfully layered TV innards, the precisely placed cinder blocks are all construction details that reveal individual care and resilience.

From the “Tijuana Comprimida” series – Photo: Ingrid Hernandez (See more images on her website.)

“Historically, images that expose households in poverty conditions contain a charged ideological baggage based on compassion, voyeurism and the tragedies of ‘others.’ I’ve been working deliberately with self-constructed houses because I want to subvert that dominant representation in social documentation,” Hernández states.

After finishing Tijuana Comprimida in 2005, Hernández taught art classes at a local university; hosted artist gatherings, talks and residencies in her home; and organized exhibitions of the work locally. In 2012, she joined with two other artists, Abraham Avila and Mayra Huerta, to open an art school, Relaciones Inesperadas (Unexpected Relations). The school now offers programs in contemporary art, cinematography and a masters in arts administration.

She has also completed many projects using the same methodology as Tijuana Comprimida to reveal the heart of a community through photography and texts. In 2009, she worked in the Nuevo Milenio 2000 (New Millenium) neighborhood to produce her Indoor series.

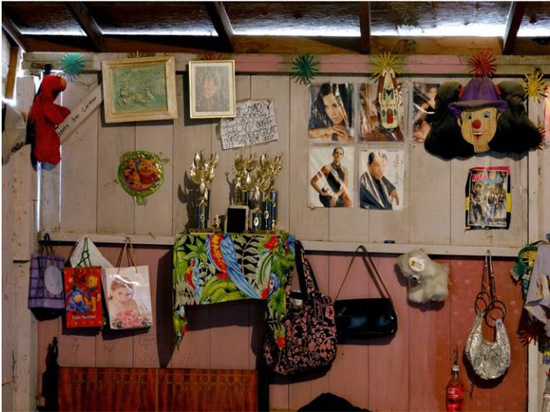

Photo from “Indoors at Nuevo Milenio 2000” series – Photo: Ingrid Hernández (See more images from this series on her website.)

For this project, Hernández took her interviews and photography inside homes and looked for the intimate decisions that people make about decorating their home – what they make central and what that says about their values.

Then, for Dentro, Nueva York (Inside, New York) she went to New York in 2011 to interview and document the homes of Mexicans who have moved there. “I had this hypothesis,” she said, “that we have an identity apart from the things we keep in our homes.”

Image from Dentro, Nueva York of an immigrant’s basement apartment in New York – Photo by Ingrid Hernández (See a gallery of images from this series at the bottom of this LA Times article.)

In the months that she spent in New York, she found it “incredible the way that people carry with them our way of living no matter where they go—when you look at the photos, you would think that you are in a pueblo; you would never believe that you were looking at NY.” Through her work, we have a way to recognize the individuals in groups of people—immigrants and laborers—who are generally discussed in dismissive terms and stereotypes.

In Hernández’ most recent project, Nada Que Declarar (Nothing To Declare), she collaborated with Pieter Wisse and people waiting to cross the border. She had the idea, she said, to work in the language of publicity as a way to reflect on the border. The two artists invited people waiting to cross share photos they had taken to be used in Nada Que Declarar. They created a Facebook page for people to upload photos they had taken while waiting to cross.

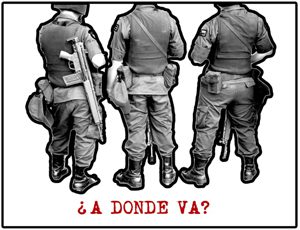

Poster from Nada Que Declarar by Ingrid Hernández and Pieter Wisse

After people had posted photos, Hernández and Wisse went through them and combined selected images with text that they found on billboards and signs that are aimed at people crossing over. For example, they added “?A donde va?” (Where are you going?) to an image taken of the backs of three heavily armed Border Patrol agents.

It is a question that everyone crossing is asked and the image and text together comment on the constant surveillance of those waiting to cross. After Hernández and Wisse had combined text and image, the two artists made large posters and handed out 500 posters to people waiting in line to cross over.

For her next project, Hernández will be working in another unincorporated community whose residents managed to buy land from the government for their neighborhood. The government agreed to sell them land, but it was not the land that they had already developed, so they had to move. Hernández points out that “usually when you own your own land, your life gets better. But for them, it is the same or worse. I want to know why.”

About Michelle Marie Robles Wallace

Michelle Marie Robles Wallace writes about the border, art, health and science. Michelle has an MFA, is a recipient of a San Francisco Writers’ Grotto Writing Fellowship, a San Francisco Arts Commission Individual Artist Grant and is an alum of Voice of Our Nation and The Community of Writers at Squaw Valley. She seems to be perennially mid-way through writing her first book but keeps herself invigorated by climbing rocks and mountains. Visit her website at: www.michellemariewallace.com